We observe all the rapid fire social media content, but really don’t get much of a chance to see the big picture. All observational sciences need tools to, well, observe. As an example, breakthroughs in astronomy depend on ever bigger and better telescopes. Studying cell biology was impossible before the development of microscopes. The social sciences have, however, so far lacked similar instruments and were limited to smaller scale behavioral studies, often in artificial laboratory settings. Recently, through the advent of social media in general and Twitter in particular this has changed. Now social scientists finally have their “socioscope” and can study the behavior of millions of people at the click of a button.

Yelena Mejova and Ingmar Weber, Qatar Computing Research Institute colleagues, are co-editors of the new book with Michael Macy: Twitter: A Digital Socioscope. I asked them a few questions to learn more about their observations and research:

What inspires you about researching Twitter and social media data?

Ingmar: I’m always amazed by how rich a data source Twitter is. Though social media definitely does not represent the whole population and though there are definitely data quality issues, numerous studies have found robust and consistent links between chatter on Twitter and quantitative real world indicators. Studying this link between the physical world and the online world lies at the heart of my research and is also at the core of our book.

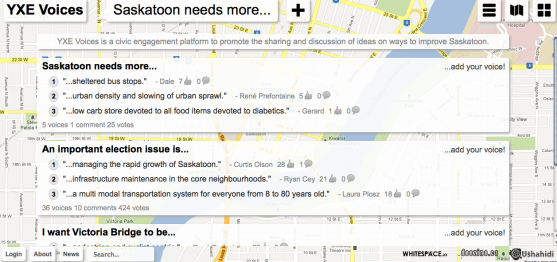

Yelena: The combination of mundane and sophisticated content on Twitter allows for a great variety in possible studies. On one side it is a space for discussion of political and community issues, while on the other the everyday life updates allow us to glimpse the diets, health, and mood of populations at scales unprecedented in social studies.

Can you share some of your core observations regarding the themes of your new book?

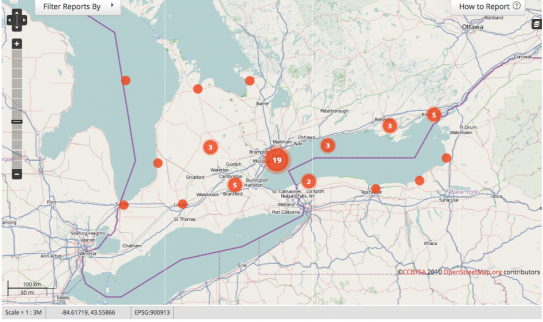

Ingmar: The overarching observation is that Twitter data can indeed provide meaningful insights about the real world. Applications range from tracking disease outbreaks to predicting the stock price. Each chapter provides a number of cases to demonstrate the feasibility, but also to question how reliable the derived information really is. For example, when it comes to tracking public opinion, caution is advised and Twitter might not be the preferred medium to analyze. Generally, in areas where one would expect the discussion to be dominated by pundits, commercial entities or by spammers extra care is needed before jumping to any conclusions because of certain trends on Twitter.

Yelena: Indeed, the chapters are written by the experts in their area, who describe the best tools for their aims, but also outline the shortcomings of the data and potential ways to overcome them. The most important observation for me is, despite the new tools and techie jargon, the methods of proper sampling, statistical analysis, and data quality checks developed throughout the social sciences are what make big data analysis a science.

What are you currently researching?

Ingmar & Yelena: We are currently looking at how to use social media data to study both public and individual health. More specifically, we are looking at how to combine data from social media with data obtained through mobile sensors, such as pedometers, to develop personalized and culturally aware interventions. Here in Qatar, changes in lifestyle have led to an explosion in obesity rates. At the same time, most of the research that looks at how to motivate people to live a healthier life considers only Western countries. We believe that the widespread use of social media such as Instagram could provide us with a tool to both gather data and advocate behavioral changes.

What can you recommend for students and data scientists to get started in this field?

Yelena: Because of the availability of both open-source tools and public data APIs, one really learns data science by “doing it”. Start with a simple question, gather data, apply algorithm, examine output, iterate. Every step helps you learn the tools of the trade, spurs more questions, and provides ground for further conversation with collaborators.

Ingmar: I think strong quantitative skills are a good foundation. This includes hands-on experience in data collection and analysis, but also in statistics and machine learning. At the same time, research in Computational Social Science is of a very interdisciplinary nature. So I’d encourage anybody to try and attend talks from other domains and to talk to experts in the humanities. Without having domain expertise on the research team it is less likely to provide new insights and it will be very hard to have actual impact.

Buy their book here to learn more! (This is my upcoming weekend read.)

About Yelena and Ingmar

Yelena Mejova (@yelenamm) is a scientist in the Social Computing Group at Qatar Computing Research Institute. Specializing in text retrieval and mining, Yelena is interested in building tools for tracking real-life social phenomena in social media. Her work on sentiment classification and evaluation, as well as political opinion tracking and poll now-casting has appeared in international computer and web science conferences such as ICWSM, WebSci and WSDM, and she is a co-editor of a Social Science Computing Review special issue on “Quantifying Politics Using Online Data”.

Ingmar Weber (@ingmarweber) is a senior scientist in the Social Computing group at Qatar Computing Research Institute. In his research, he uses large amounts of online data from Twitter and other sources to study phenomena that affect society at large. Recent work has looked at political polarization in Egypt, at global gender inequality in online social networks, at international migration, at relationship breakups, and at food consumption and obesity seen through social media. His research is frequently featured in popular press such as the Washington Post, Forbes, NewScientist, Financial Times, or Foreign Policy.